Part 1: Public defence shipyards bag 85-95% of warship orders without tendering

Ficci asks Rajnath Singh for level playing field for private shipyards

By Ajai Shukla

Business Standard, 5th Aug 19

(Photo: Mazagon Docks' modular infrastructure, built at public expense)

(Photo: Mazagon Docks' modular infrastructure, built at public expense)

The Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (Ficci) has written a strongly-worded note to Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, asking the ministry of defence (MoD) to end the practice of “nominating” defence public sector undertaking (DPSU) shipyards to build warships for the navy and coast guard.

“Nomination” involves placing orders for warships on chosen public sector shipyards, without competitive tendering. Ficci’s note asks for a level playing field for private shipyards by permitting them to participate in all warship tenders.

Private defence shipyards are in dire straits, with two of them – Bharati and ABG Shipyards – facing foreclosure; and sparse order books for the others, despite L&T’s Rs 3,500 crore construction of a Greenfield shipyard at Katupalli, Tamil Nadu, and Reliance Naval and Engineering’s Rs 2,000 crore purchase of Pipavav Shipyard.

Ficci has presented figures to highlight that, over the last two decades, the four DPSU shipyards – Mazagon Dock Ltd, Mumbai (MDL), Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers (GRSE), Goa Shipyard Ltd (GSL) and Hindustan Shipyard Ltd, Visakhapatnam (HSL) – along with Kerala state’s Cochin Shipyard Ltd (CSL), garnered all the high-value orders through “nomination”.

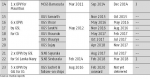

Between 2000-2010, PSU yards were “nominated” for over 95 per cent by value of all warship orders, amounting to Rs 76,794 crore. Only 4.9 per cent of orders were competitively tendered. Of those, PSU yards won 1.9 per cent (worth Rs 1,500 crore) while private yards won the remaining three per cent, worth Rs 2,446 crore.

The MoD counters that most warship orders are competitively tendered. It says PSU yards were “nominated” to build only 56 ships, while the private sector was allowed to participate in the tendering for 90 ships – 62 per cent of the total numbers.

While that is so, the 38 per cent of orders that were “nominated” to PSU yards included all the high-value warships, adding up to 95 per cent of the monetary value. The 62 per cent where the private sector competed involved small, low-value auxiliary vessels.

Ficci further contends that, with PSU yards having pocketed 95 per cent of orders through “nomination”, they possessed ample resources to cross-subsidise their bids in the remaining orders that were competitively tendered. Consequently, private shipyards had to resort to “gross underbidding just to remain in business,” says Ficci.

In November 2010, then defence minister AK Antony had pledged: “From January 2011onwards, the Defence Acquisition Council (DAC) will not give any nominations to the defence shipyards for naval projects and they will have to compete with the private shipyards for the tenders.”

Yet, little changed in practice. Between 2011-19, PSU shipyards were “nominated” for 85 per cent by value of shipbuilding contracts, constituting Rs 146,261 crore. The private sector participated in just 15 per cent of the tenders, worth Rs 25,758 crore.

With huge contracts already in hand, says Ficci, “The PSUs began resorting to rampant cross subsidization to win 10.4 per cent programmes, leaving a meagre 4.6 per cent for the private sector.”

Once again, absolute figures are misleading. Between 2011-19, contracts to build 73 warships were awarded after competitive bidding, while 69 warships were “nominated” to public sector yards. However, the latter included all the lucrative warship contracts, leaving private shipyards to compete only in orders for low-value, auxiliary vessels.

Ficci has also raised another point with operational implications: The large volume of “nominated” orders placed on PSU shipyards has created such a huge order backlog that the navy and coast guard will have to wait many years for delivery of warships.

Last week Business Standard reported (July 30,

Garden Reach builds 100th warship; order book full for next 20 years) that GRSE would take 20 years to discharge its order book of Rs 27,500 crore, at its current annual turnover of Rs 1,386 crore.

According to MoD figures, the combined value of production in 2017-18 of MDL, GRSE, GSL and HSL added up to just Rs 7,600 crore. Yet they were “nominated” during the last two decades for warship orders worth Rs 223,055 crore.

“With this rate of execution, gross delays are inevitable in liquidation of existing order book thus affecting warship induction plans and force readiness levels of the Indian Navy,” said Ficci.

Citing a report that the Prime Minister’s Office has mandated that all future warship contracts will be competitively bid, Ficci has requested that no new orders should be “nominated” to PSU shipyards. Further, on-going “nominated” procurements in which contracts have not yet been awarded must be re-categorized and re-bid, with private shipyards participating.

As a key enabler for private shipbuilding, Ficci has requested that the Strategic Partnership (SP) procurement model be fast-tracked for Project 75-I, which involves constructing six conventional submarines for the navy. That would require the MoD to choose an Indian private shipyard to build the six submarines in India in technology partnership with a global “original equipment manufacturer” (OEM).

Ficci has cautioned against allowing DPSU yards into SP projects, which the MoD is considering. Instead the MoD is urged to stick with the “original intent of SP model being reserved for participation by the private sector only.”

The original SP concept that the Dhirendra Singh Committee (2015) and VK Aatrey Task Force (2016) envisioned has the primary objective of developing private sector capabilities in defence manufacturing. However, the SP policy that the MoD eventually drew up for the Defence Procurement Procedure of 2016 (DPP-2016), left the door open for DPSUs to compete in SP category procurements.

Ficci argues that private shipbuilders cannot compete on level terms with PSU yards. The latter have benefited from hundreds of crores of government funds spent on their modernisation and on technology transferred over earlier “nominated” contracts.

“In case [the Project 75-I procurement on the SP model cannot be restricted to the private sector], the competing DPSU bids must be loaded for the cross-subsidy arbitrage in the form of free access to government funded assets and past repeated ToTs (transfer of technology),” says Ficci.

Broadsword: Part 1: Public defence shipyards bag 85-95% of warship orders without tendering