I can tell you that this will immensely benefit India and make us the real regional superpower in Asia above China.Well, we will look out for our own interests at the end of the day. The Indian economy needs to reorient to meet the threat of closing economies, with tariffs and barriers coming up everywhere slowly.

Indian Economy : News,Discussions & Updates

- Thread starter Butter Chicken

- Start date

-

- Tags

- indian defence forum

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wait, how ? Imposing tariffs on imports worth some 200 odd millions will make us a regional super power ?I can tell you that this will immensely benefit India and make us the real regional superpower in Asia above China.

This is good initiative, if followed through.

Israel ready to help India in dealing with water shortage

Israel ready to help India in dealing with water shortage

@Nilgiri Your views on his methodology and conclusions. (His paper )India’s GDP growth: New evidence for fresh beginnings

Methodological changes have led to overestimating GDP growth by 2.5 percentage points per year between 2011-12 and 2016-17. Actual growth is around 4.5 per cent.

The promise of democracy is the periodic opportunity it creates for fresh beginnings. A government re-elected with such a resounding mandate should continue with the successful aspects of its economic policies. The most notable has been promoting economic inclusion via the public provision of essential private goods and services, including toilets, housing, power, cooking gas, bank accounts, emergency medical assistance, and now a basic income for all farmers.

But that mandate should also embolden change in other aspects, based on new evidence and fresh understanding. My new research suggests that post-global financial crisis, the heady narrative of a guns-blazing India — that statisticians led us to believe — may have to cede to a more realistic one of an economy growing solidly but not spectacularly.

My results indicate that methodological changes led to GDP growth being overstated by about 2.5 percentage points per year between 2011-12 and 2016-17, a period that spans both UPA and NDA governments. Official estimates place average annual growth for this period at about 7 per cent. Actual growth may have been about 4.5 per cent, with a 95 per cent confidence interval of 3.5 to 5.5 per cent.

A few important clarifications. Much of the recent commentary has portrayed these changes as political, since they were announced late in 2014 after the NDA-2 government came into power, and because there have been other, more recent GDP controversies, such as the back-casting exercise, and puzzling upward revisions for the most recent years. But the methodological changes, which did not originate from the politicians, must be distinguished from these recent controversies. The substantive work was done by technocrats, and largely under the UPA-2 government.

Moreover, the effort was desirable, both to expand the data for GDP estimation and to move to a methodology more suited for a technologically advancing, dynamic economy. The non-politicised nature of the changes can be seen from the fact that the new estimates bumped up growth for 2013-14, the last year of the UPA-2 government.

The research paper provides a variety of evidence on mis-estimation, but here I discuss two strands. First, I compile 17 key indicators for the period 2001-02 to 2017-18 that are typically correlated with GDP growth: Electricity consumption, two-wheeler sales, commercial vehicle sales, tractor sales, airline passenger traffic, foreign tourist arrivals, railway freight traffic, index of industrial production (IIP), IIP (manufacturing), IIP (consumer goods), petroleum, cement, steel, overall real credit, real credit to industry, and exports and imports of goods and services. These indicators are also chosen because they are mostly produced independently of the CSO.

Second, I compare India with other countries. For a sample of 71 high and middle income countries, I estimate a relationship between a set of indicators and GDP growth for the pre and post-2011 periods. The indicators chosen (credit, exports, imports and electricity) are simple, reliable, and typically not produced by the agency that estimates GDP. This relationship is captured by the upward-sloping line in Figure 2. The line shows the growth predicted by the indicators (horizontal axis) and what is officially reported (vertical axis).

In the first period, the India data point (red) is bang on the line, indicating that it is a normal country: India’s reported GDP growth is consistent with the cross-country relationship. However, in the second period the India data point (blue) is well above the line, implying that its GDP growth is much greater than what would be predicted by the cross-country relationship — by over 2.5 percentage points per year. This shifting pattern across the two periods — India being normal in the first, but an outlier in the second — is a robust result, not depending on samples, indicators, or estimation procedures.

Reproducing the detailed methodology underlying the GDP estimates is impossible for outside researchers, so it is difficult to trace the source of the problem. But we can locate one sector where the mis-measurement seems particularly severe, namely formal manufacturing. Before 2011, formal manufacturing value added from the national income accounts moved closely with IIP (Mfg.) and with manufacturing exports. But afterward the correlations turn strongly and bizarrely negative.

Further research, building on this paper will surely uncover further insights. Accordingly, I will soon make the data and codes underlying this paper public for further analysis.

What are the implications of these findings? Growth estimates matter not just for reputational reasons but critically for internal policy-making. The new evidence implies that both monetary and fiscal policies over the last years were overly tight from a cyclical perspective. For example, interest rates may have been too high, by as much as 150 basis points. The Indian policy automobile has been navigated with a faulty, possibly broken, speedometer.

In addition, inaccurate statistics on the economy’s health dampen the impetus for reform. For example, had it been known that India’s GDP growth was actually 4.5 per cent, the urgency to act on the banking system or on agricultural challenges may have been greater.

Most important, restoring growth must be the key policy objective. Policy discourse recently has focused on employment, agriculture and redistribution more broadly. The popular narrative has been one of “jobless growth”, hinting at a disconnect between fundamental dynamism and key outcomes. In reality, weak job growth and acute financial sector stress may have simply stemmed from modest GDP growth. Going forward, there must be reform urgency stemming from the new knowledge that growth has been tepid, not torrid; And from recognising that growth of 4.5 per cent will make the government’s laudable inclusion agenda difficult to sustain fiscally.

Another obvious implication is that GDP estimation in its entirety must be revisited by an independent task force, comprising both national and international experts, statisticians, macro-economists and policy users. Indeed, this revisiting may throw up exciting, new opportunities, such as using the large amounts of transactions-level GST data that is now being generated, to estimate — for the first time in India — expenditure-based estimates of GDP.

Finally, the question will arise as to my role on this issue while I was CEA. Throughout my tenure, my team and I grappled with conflicting economic data. We raised these doubts frequently within government, and publicly articulated these in a measured manner in government documents, especially the Economic Survey of July 2017. But the time and space afforded by being outside government were necessary to undertake months of very detailed research, including subjecting it to careful scrutiny and cross-checking by numerous colleagues, to generate robust evidence.

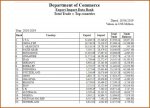

Shocking to see India only having a positive trade balance with USA n Netherlands. All countries in the top 20 list are more developed than India and we instead of having a positive trade balance are net importers.I can tell you that this will immensely benefit India and make us the real regional superpower in Asia above China.

WTO deal has brought us nothing. No harm in putting trade barriers.

Shocking to see India only having a positive trade balance with USA n Netherlands. All countries in the top 20 list are more developed than India and we instead of having a positive trade balance are net importers.

WTO deal has brought us nothing. No harm in putting trade barriers.

Attachments

It is flawed analysis by him given he essentially advocates a change globally (not only India) away from SNA 2008 simply because he feels the numbers are too high.

Also the issue of picking some set of indicators and saying they somehow form a valid estimator correlation in lieu of the actual data flow...because of personal sentiment on what GDP even is?

His indicators dont have enough services related output (given indian economy is majority services based) and he makes no account for increased productivity being a factor (or the MCA database issue leading to companies that do manufacturing listing as services instead). The latter however does need more clarification and transparency by the govt.

The interview by Karan Thapar presented the issue quite well overall:

Another pretty fair analysis (and we know SA Aiyar has criticized NDA and Modi plenty), and I would add tax data as another piece of evidence it simply cannot be as low as 4.5% growth:

View: Arvind Subramanian's GDP growth math has technical weaknesses

View: Arvind Subramanian's GDP growth math has technical weaknesses

its mainly petroleum for most of the negative trade balance countries.......Shocking to see India only having a positive trade balance with USA n Netherlands. All countries in the top 20 list are more developed than India and we instead of having a positive trade balance are net importers.

WTO deal has brought us nothing. No harm in putting trade barriers.

Pls explain to us just exactly what is his forte? I don't think even funny stuff and off topic chit chats are his forte.That's enough fun @Guynextdoor , Economics is not your forte . Take a break from this thread.

By Doug Palmer

06/19/2019 11:31 AM EDT

India could face additional U.S. trade actions unless it agrees to open its market to more U.S. exports, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer told lawmakers today.

"We have a series of problems with them," Lighthizer told the House Ways and Means Committee during a hearing on President Donald Trump's trade agenda.

Trump decided recently to kick India out the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences trade program because "we made literally no headway on the issues over the course of months and months and months," Lighthizer said.

The administration is also looking at a variety of other "unfair" Indian trade practices "which may provoke us to take some other kind — some additional action," Lighthizer said.

Lighthizer did not go into specifics. But one option could be a Section 301 investigation, similar to the action the Trump administration pursued against China before slapping duties on $250 billion of Chinese exports.

Still, Lighthizer emphasized that he hoped to resolve differences with India through dialogue. He noted Prime Minister Narendra Modi was recently reelected and has appointed a new commerce minister, Piyush Goyal.

"I will talk to him in the next few days, and it's my hope we can jump-start and make some headway," Lighthizer said. "But India has about the highest tariffs of any country you can imagine."

06/19/2019 11:31 AM EDT

India could face additional U.S. trade actions unless it agrees to open its market to more U.S. exports, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer told lawmakers today.

"We have a series of problems with them," Lighthizer told the House Ways and Means Committee during a hearing on President Donald Trump's trade agenda.

Trump decided recently to kick India out the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences trade program because "we made literally no headway on the issues over the course of months and months and months," Lighthizer said.

The administration is also looking at a variety of other "unfair" Indian trade practices "which may provoke us to take some other kind — some additional action," Lighthizer said.

Lighthizer did not go into specifics. But one option could be a Section 301 investigation, similar to the action the Trump administration pursued against China before slapping duties on $250 billion of Chinese exports.

Still, Lighthizer emphasized that he hoped to resolve differences with India through dialogue. He noted Prime Minister Narendra Modi was recently reelected and has appointed a new commerce minister, Piyush Goyal.

"I will talk to him in the next few days, and it's my hope we can jump-start and make some headway," Lighthizer said. "But India has about the highest tariffs of any country you can imagine."