From the very same document that your chart come from (Oct 18, 2022)

U.S. Air Force John Venable The mission of the U.S. Air Force has expanded significantly since 1947 when the USAF became a separate service. Initially, operations were divided among four major components—Strategic Air Command, Tactical Air Command, Air Defense Command, and Military Air Transport...

www.heritage.org

Unlike maintenance manning, the pilot shortage continues to plague the service. In March 2017, Lieutenant General Gina M. Grosso, Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff for Manpower, Personnel, and Services, testified that at the end of FY 2016, the Air Force had a shortfall of 1,555 pilots. Of that total, the Air Force was short 1,211 fighter pilots: 873 Active and 338 from the Active Reserve Component (ARC).

Even with the temporary surge in retention caused by COVID-19, the Total Force shortfall is 1,650: 650 Active and 1,000 ARC.

The Air Force graduated 1,200 pilots in FY 2018, added 1,279 in FY 2019, and projected that 1,480 would graduate in 2020, but the impact of COVID-19 was such that only 1,263 received their wings. Another 1,381 graduated in FY 2021, and the Air Force estimated that the number would be similar for FY 2022.

Those projected numbers rely on a very high annual graduation rate of approximately 94 percent of the candidates that enter flight school during any given year. According to the Air Force, the graduation rates for the past four years were 98 percent in 2018, 94 percent in 2019, 85 percent in 2020 (COVID-19), and 95.5 percent in 2021. The vast majority of those who washed out from flight school in 2021 were eliminated for health, discipline, or other reasons not specifically related to performance; only 0.27 percent were eliminated based on performance.

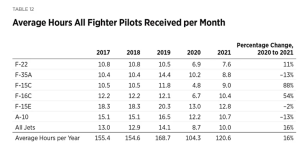

Throughout the pilot shortage, the Air Force has done an excellent job of emphasizing operational manning instead of placing experienced fighter pilots at staffs and schools, but the currency and qualifications of the pilots in operational units are at least as important as manning levels. Although the quality of sorties is admittedly subjective, a healthy rate of three sorties a week and flying hours averaging more than 200 hours a year have been established as “sufficient” over more than six decades of fighter pilot training.

In the words of General Bill Creech, “Higher sortie rates mean increased proficiency for our combat aircrews,”

and given the right number of sorties and quality flight time, it takes seven years beyond mission qualification in a fighter for an individual to maximize his potential as a fighter pilot.

COVID-19’s impact on flying hours hit the Air Force as it was beginning to recover from an 18-year drought in training for combat with a near-peer competitor. Flying hours and sortie rates across all fighter platforms fell to historic lows as the average line combat mission-ready fighter pilot received less than 1.4 sorties a week and 131 hours of flying time per year.

74

Those numbers increased only marginally in 2021 to 1.5 sorties a week and 133.3 hours of flight time per year, not much above the all-time lows experienced the preceding year. That equates to roughly two-thirds the number of sorties required to meet the minimum sortie threshold to qualify pilots as combat mission capable throughout the Combat Air Force (CAF).

Those numbers are so low in a high-performance fighter that pilot competence levels drop to the point where even excellent pilots begin to question their execution of very basic tasks and where the execution of complex mission tasks can become overwhelming.75

In a speech delivered on September 21, 2022, General Mark Kelly stated that the average fighter pilot received just 6.8 hours of flying time per month for a total of 81.6 hours of flying time in 2021.

76

No matter which data point is selected, the numbers reflect an Air Force that would struggle in a fight with a regional competitor and founder in a war with a peer adversary.